I don’t think I need to convince you that testing your JavaScript code is a good idea. But, it can sometimes prove tedious to test JavaScript code that requires a DOM. This means you need to test your code in the browser and can’t use the terminal, right? Wrong, actually: enter PhantomJS.

What exactly is PhantomJS? Well, here’s a blurb from the PhantomJS website:

PhantomJS is a headless WebKit with JavaScript API.

As you know, Webkit is the layout engine that Chrome, Safari, and a few other niche browsers use. So PhantomJS is a browser, but a headless browser. This means that the rendered web pages are never actually displayed. This may sound weird to you; so you can think of it as a programmable browser for the terminal. We’ll look at a simple example in a minute, but we first need to install PhantomJS.

Installing PhantomJS

Installing PhantomJS is actually pretty simple: it’s just a single binary that you download and stick in your terminal path. On the PhantomJS download page, choose your operating system and download the correct package. Then move the binary file from the downloaded package to a directory inside your terminal path (I like to put this kind of thing in ~/bin).

If you’re on Mac OS X, there’s a simpler way to install PhantomJS (and this is actually the method I used). Just use Homebrew, like this:

brew update && brew install phantomjs

You should now have PhantomJS installed. You can double-check your installation by running this:

phantomjs --version

I’m seeing 1.7.0; you?

A Small Example

Let’s start with a small example.

simple.js

console.log("we can log stuff out.");function add(a, b) { return a + b;}conslole.log("We can execute regular JS too:", add(1, 2));phantom.exit(); Go ahead and and run this code by issuing the following command:

phantomjs simple.js

You should see the output from the two console.log lines in your terminal window.

Sure, this is simple, but it makes a good point: PhantomJS can execute JavaScript just like a browser. However, this example doesn’t have any PhantomJS-specific code…well, apart from the last line. That’s an important line for every PhantomJS script because it exits the script. This might not make sense here, but remember that JavaScript doesn’t always execute linearly. For example, you might want to put the exit() call in a callback function.

Let’s look at a more complex example.

Loading Pages

Using the PhantomJS API, we can actually load any URL and work with the page from two perspectives:

- as JavaScript on the page.

- as a user looking at the page.

Let’s start by choosing to load a page. Create a new script file and add the following code:

script.js

var page = require('webpage').create();page.open('http://net.tutsplus.com', function (s) { console.log(s); phantom.exit();}); We start by loading PhantomJS’ webpage module and creating a webpage object. We then call the open method, passing it a URL and a callback function; it’s inside this callback function that we can interact with the actual page. In the above example, we just log the status of the request, provided by the callback function’s parameter. If you run this script (with phantomjs script.js), you should get ‘success’ printed in the terminal.

But let’s make this more interesting by loading a page and executing some JavaScript on it. We start with the above code, but we then make a call to page.evaluate:

page.open('http://net.tutsplus.com', function () { var title = page.evaluate(function () { var posts = document.getElementsByClassName("post"); posts[0].style.backgroundColor = "#000000"; return document.title; }); page.clipRect = { top: 0, left: 0, width: 600, height: 700 }; page.render(title + ".png"); phantom.exit();}); PhantomJS is a browser, but a headless browser.

The function that we pass to page.evaluate executes as JavaScript on the loaded web page. In this case, we find all elements with the post class; then, we set the background of the first post to black. Finally, we return the document.title. This is a nice feature, returning a value from our evaluate callback and assigning it to a variable (in this case, title).

Then, we set the clipRect on the page; these are the dimensions for the screenshot we take with the render method. As you can see, we set the top and left values to set the starting point, and we also set a width and height. Finally, we call page.render, passing it a name for the file (the title variable). Then, we end by calling phantom.exit().

Go ahead and run this script, and you should have an image that looks something like this:

You can see both sides of the PhantomJS coin here: we can execute JavaScript from inside the page, and also execute from the outside, on the page instance itself.

This has been fun, but not incredibly useful. Let’s focus on using PhantomJS when testing our DOM-related JavaScript.

Testing with PhantomJS

Yeoman uses PhantomJS in its testing procedure, and it’s virtually seamless.

For a lot of JavaScript code, you can test without needing a DOM, but there are times when your tests need to work with HTML elements. If you’re like me and prefer to run tests on the command line, this is where PhantomJS comes into play.

Of course, PhantomJS is not a testing library, but many of the other popular testing libraries can run on top of PhantomJS. As you can see from the PhantomJS wiki page on headless testing, PhantomJS test runners are available for pretty much every testing library you might want to use. Let’s look at how to use PhantomJS with Jasmine and Mocha.

First, Jasmine and a disclaimer: there isn’t a good PhantomJS runner for Jasmine at this time. If you use Windows and Visual Studio, you should check out Chutzpah, and Rails developers should try guard-jasmine. But other than that, Jasmine+PhantomJS support is sparse.

For this reason, I recommend you use Mocha for DOM-related tests.

HOWEVER.

It’s possible that you already have a project using Jasmine and want to use it with PhantomJS. One project, phantom-jasmine, takes a little bit of work to set up, but it should do the trick.

Let’s begin with a set of JasmineJS tests. Download the code for this tutorial (link at the top), and check out the jasmine-starter folder. You’ll see that we have a single tests.js file that creates a DOM element, sets a few properties, and appends it to the body. Then, we run a few Jasmine tests to ensure that process did indeed work correctly. Here’s the contents of that file:

tests.js

describe("DOM Tests", function () { var el = document.createElement("div"); el.id = "myDiv"; el.innerHTML = "Hi there!"; el.style.background = "#ccc"; document.body.appendChild(el); var myEl = document.getElementById('myDiv'); it("is in the DOM", function () { expect(myEl).not.toBeNull(); }); it("is a child of the body", function () { expect(myEl.parentElement).toBe(document.body); }); it("has the right text", function () { expect(myEl.innerHTML).toEqual("Hi there!"); }); it("has the right background", function () { expect(myEl.style.background).toEqual("rgb(204, 204, 204)"); });}); The SpecRunner.html file is fairly stock; the only difference is that I moved the script tags into the body to ensure the DOM completely loads before our tests run. You can open the file in a browser and see that all the tests pass just fine.

Let’s transition this project to PhantomJS. First, clone the phantom-jasmine project:

git clone git://github.com/jcarver989/phantom-jasmine.git

This project isn’t as organized as it could be, but there are two important parts you need from it:

- the PhantomJS runner (which makes Jasmine use a PhantomJS DOM).

- the Jasmine console reporter (which gives the console output).

Both of these files reside in the lib folder; copy them into jasmine-starter/lib. We now need to open our SpecRunner.html file and adjust the <script /> elements. Here’s what they should look like:

<script src="lib/jasmine-1.2.0/jasmine.js"></script><script src="lib/jasmine-1.2.0/jasmine-html.js"></script><script src="lib/console-runner.js"></script><script src="tests.js"></script><script> var console_reporter = new jasmine.ConsoleReporter() jasmine.getEnv().addReporter(new jasmine.HtmlReporter()); jasmine.getEnv().addReporter(console_reporter); jasmine.getEnv().execute();</script>

Notice that we have two reporters for our tests: an HTML reporter and a console reporter. This means SpecRunner.html and its tests can run in both the browser and the console. That’s handy. Unfortunately, we do need to have that console_reporter variable because it’s used inside the CoffeeScript file we’re about to run.

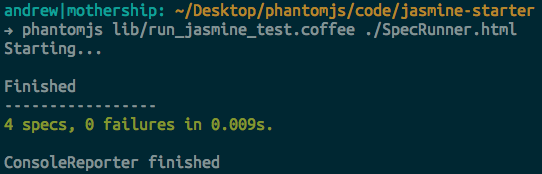

So, how do we go about actually running these tests on the console? Assuming you’re in the jasmine-starter folder on the terminal, here’s the command:

phantomjs lib/run\_jasmine\_test.coffee ./SpecRunner.html

We’re running the run\_jasmine\_test.coffee script with PhantomJS and passing our SpecRunner.html file as a parameter. You should see something like this:

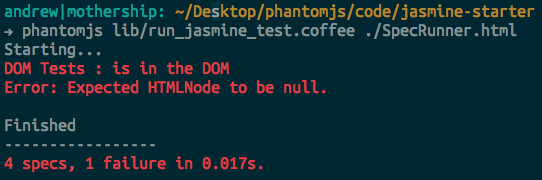

Of course, if a test fails, you’ll see something like the following:

If you plan on using this often, it might be a good idea to move run\_jasmine\_test.coffee to another location (like ~/bin/run\_jasmine\_test.coffee) and create a terminal alias for the whole command. Here’s how you’d do that in a Bash shell:

alias phantom-jasmine='phantomjs /path/to/run\_jasmine\_test.coffee'

Just throw that in your .bashrc or .bash_profile file. Now, you can just run:

phantom-jasmine SpecRunner.html

Now your Jasmine tests work just fine on the terminal via PhantomJS. You can see the final code in the jasmine-total folder in the download.

PhantomJS and Mocha

Thankfully, it’s much easier to integrate Mocha and PhantomJS with mocha-phantomjs. It’s super-easy to install if you have NPM installed (which you should):

npm install -g mocha-phantomjs

This command installs a mocha-phantomjs binary that we’ll use to run our tests.

In a previous tutorial, I showed you how to use Mocha in the terminal, but you’ll do things differently when using it to test DOM code. As with Jasmine, we’ll start with an HTML test reporter that can run in the browser. The beauty of this is we’ll be able to run that same file on the terminal for console test results with PhantomJS; just like we could with Jasmine.

So, let’s build a simple project. Create a project directory and move into it. We’ll start with a package.json file:

{ "name": "project", "version": "0.0.1", "devDependencies": { "mocha": "*", "chai" : "*" }} Mocha is the test framework, and we’ll use Chai as our assertion library. We install these by running NPM.

We’ll call our test file test/tests.js, and here are its tests:

describe("DOM Tests", function () { var el = document.createElement("div"); el.id = "myDiv"; el.innerHTML = "Hi there!"; el.style.background = "#ccc"; document.body.appendChild(el); var myEl = document.getElementById('myDiv'); it("is in the DOM", function () { expect(myEl).to.not.equal(null); }); it("is a child of the body", function () { expect(myEl.parentElement).to.equal(document.body); }); it("has the right text", function () { expect(myEl.innerHTML).to.equal("Hi there!"); }); it("has the right background", function () { expect(myEl.style.background).to.equal("rgb(204, 204, 204)"); });}); They’re very similar to the Jasmine tests, but the Chai assertion syntax is a bit different (so, don’t just copy your Jasmine tests).

The last piece of the puzzle is the TestRunner.html file:

<html> <head> <title> Tests </title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="./node_modules/mocha/mocha.css" /> </head> <body> <div id="mocha"></div> <script src="./node_modules/mocha/mocha.js"></script> <script src="./node_modules/chai/chai.js"></script> <script> mocha.ui('bdd'); mocha.reporter('html'); var expect = chai.expect; </script> <script src="test/test.js"></script> <script> if (window.mochaPhantomJS) { mochaPhantomJS.run(); } else { mocha.run(); } </script> </body></html> There are several important factors here. First, notice that this is complete enough to run in a browser; we have the CSS and JavaScript from the node modules that we installed. Then, notice the inline script tag. This determines if PhantomJS is loaded, and if so, runs the PhantomJS functionality. Otherwise, it sticks with raw Mocha functionality. You can try this out in the browser and see it work.

To run it in the console, simply run this:

mocha-phantomjs TestRunner.html

Voila! Now you’re tests run in the console, and it’s all thanks to PhantomJS.

PhantomJS and Yeoman

I’ll bet you didn’t know that the popular Yeoman uses PhantomJS in its testing procedure, and it’s vritually seemless. Let’s look at a quick example. I’ll assume you have Yeoman all set up.

Create a new project directory, run yeoman init inside it, and answer ‘No’ to all the options. Open the test/index.html file, and you’ll find a script tag near the bottom with a comment telling you to replace it with your own specs. Completely ignore that good advice and put this inside the it block:

var el = document.createElement("div");expect(el.tagName).to.equal("DIV"); Now, run yeoman test, and you’ll see that the test runs fine. Now, open test/index.html file in the browser. It works! Perfect!

Of course, there’s a lot more you can do with Yeoman, so check out the documentation for more.

Conclusion

Use the libraries that extend PhantomJS to make your testing simpler.

If you’re using PhantomJS on its own, there isn’t any reason to learn about PhantomJS itself; you can just know it exists and use the libraries that extend PhantomJS to make your testing simpler.

I hope this tutorial has encouraged you to look into PhantomJS. I recommend starting with the example files and documentation that PhantomJS offers; they’ll really open your eyes to what you can do with PhantomJS–everything from page automation to network sniffing.

So, can you think of a project that PhantomJS would improve? Let’s hear about it in the comments!

Source : internetwebsitedesign[dot]biz

0 comments:

Post a Comment